The report contains data on nearly 1,200 species, of which 391 are included in the threat categories on the IUCN Red List: 90 are critically endangered, 121 are endangered and 180 are vulnerable.

"The reduction and possible extinction of these vertebrate species threatens the health of entire ocean ecosystems and the food security of many nations around the world," warns Professor Nicholas Dulvy from Simon Fraser University in Canada.

41% of the 611 known species of rays or rajiformes are under threat; 36% of the 536 recorded species of sharks or sela-cimorphs and 9% of the 52 species of chimeras.

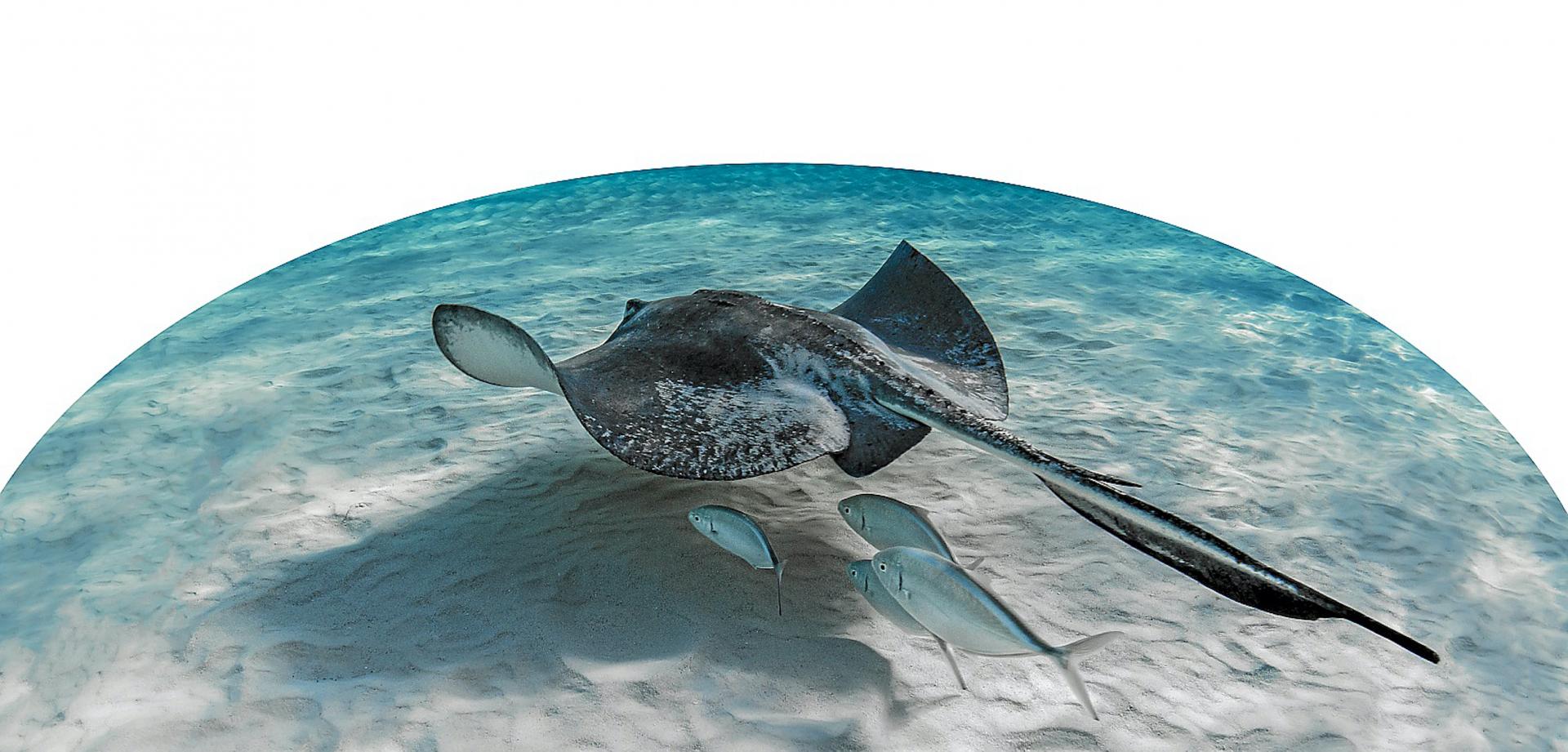

Stingrays are the most endangered fish amongst the chondrichthyans class, whose skeleton is made of cartilage instead of bone and sawfish, giant guitarfish, devil rays and pelagic eagle rays are also under threat.

Dulvy welcomes the fact that the number of scientific contributions on chondrichthyans has doubled in recent years, which makes it easier to achieve a more accurate global analysis of their status, but he paints a grim picture of what he considers "one of the most endangered vertebrates on the planet."

Investigation

The research lasted eight years and involved 322 experts, whose evaluations showed that chondrichthyans are exceptionally vulnerable to overfishing, because they grow very slowly and have very few offspring.

Squares and rays are highly valued commercially and are caught for their meat, skin, fins and gills and used in various spearfishing and diving activities.

“Their overexploitation has exceeded the effective management of resources,” according to the report, not to mention the degradation of their habitat and the effects of climate change and pollution.

The researchers who participated in the report accuse Governments of “doing very little to alleviate the risks faced by these species, because they do not pay attention to the scientific advice, which recommends minimising their mortality and ending their exploitation.”

“The greatest threat to this type of species is intensive fishing for more than a century by fleets that are committed to improving, but are still poorly managed,” said Assistant Professor Colin Simpfendorfer from James Cook University in Australia.

No comments

To be able to write a comment, you have to be registered and logged in

Currently there are no comments.